(Sigue de la entrada Aprenda un poco de inglés con… Gian-Carlo Rota (1/11))

1 Lecturing

The following four requirements of a good lecture do not seem to be altogether obvious, judging from the mathematics lectures I have been listening to for the past forty-six years.

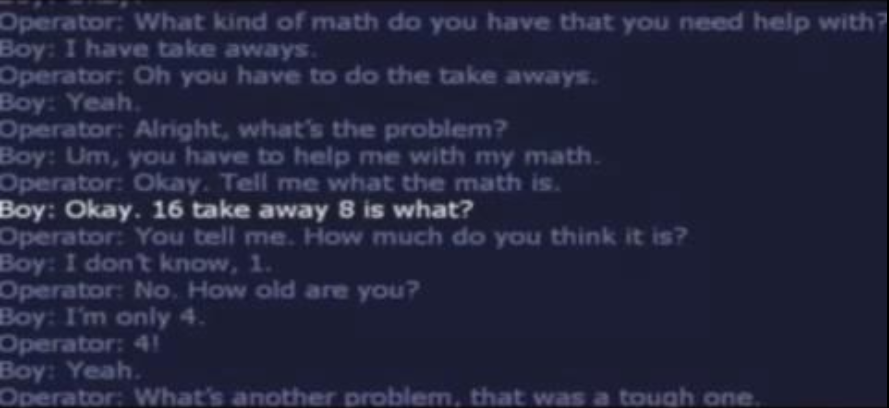

a. Every lecture should make only one main point The German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel wrote that any philosopher who uses the word “and” too often cannot be a good philosopher. I think he was right, at least insofar as lecturing goes. Every lecture should state one main point and repeat it over and over, like a theme with variations. An audience is like a herd of cows, moving slowly in the direction they are being driven towards. If we make one point, we have a good chance that the audience will take the right direction; if we make several points, then the cows will scatter all over the field. The audience will lose interest and everyone will go back to the thoughts they interrupted in order to come to our lecture.

b. Never run overtime Running overtime is the one unforgivable error a lecturer can make. After fifty minutes (one microcentury as von Neumann used to say) everybody’s attention will turn elsewhere even if we are trying to prove the Riemann hypothesis. One minute overtime can destroy the best of lectures.

c. Relate to your audience As you enter the lecture hall, try to spot someone in the audience with whose work you have some familiarity. Quickly rearrange your presentation so as to manage to mention some of that person’s work. In this way, you will guarantee that at least one person will follow with rapt attention, and you will make a friend to boot.Everyone in the audience has come to listen to your lecture with the secret hope of hearing their work mentioned.

d. Give them something to take home It is not easy to follow Professor Struik’s advice. It is easier to state what features of a lecture the audience will always remember, and the answer is not pretty. I often meet, in airports, in the street and occasionally in embarrassing situations, MIT alumni who have taken one or more courses from me. Most of the time they admit that they have forgotten the subject of the course, and all the mathematics I thought I had taught them. However, they will gladly recall some joke, some anecdote, some quirk, some side remark, or some mistake I made.